Appropriation in Ayurveda

By Dr. Ramkumar, Dr. Robert Svoboda & Dr. Claudia Welch

Note: This is an evolving work. We have already changed the title and edited the article a bit in response to thoughtful input from readers. We have added links at the bottom of this article to other sources that cover some of the important issues of cultural appropriation in Ayurveda that we do not cover in this article.

In these times of generalized upheaval in societies worldwide the issue of appropriation, which we can define as the adoption of components of one culture by members of another, has attracted widespread attention. This process of adoption, which may on occasion be benign or even beneficial, is often harmful. Because Ayurveda is a system of health and healing that originated in India but is now becoming global, the question of appropriation of Ayurveda needs to be addressed.

While there are many ways Indian culture has been appropriated– and often selectively evolved –to suit a white, Western culture, and some issues of cultural appropriation may well overlap with those related to the Black experience in the USA, feel urgent, and be important, this paper is not intended to be a comprehensive look at all aspects of cultural appropriation. It is, in fact, only a response to Western students’ requests for us to explore how Ayurveda should be learned, practiced and taught outside of its birthplace–India, if indeed it should.

Sociologists identify the material and the non-material as two intimately connected yet separate aspects of a culture. A culture’s non-material values, beliefs, language, laws and symbols influence — and are influenced by — the material nature of what they do and make; how they behave; and the objects they manufacture. While cultural appropriation of both material and non-material cultural aspects must therefore usually be examined, this does not apply to Ayurveda as its theory and practice are concurrently and inherently connected (i.e. they enjoy a samavāyi sambandha).

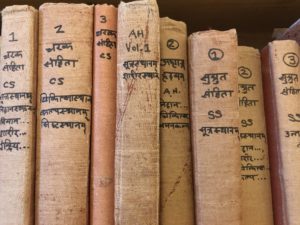

A distinction does however have to be drawn between that knowledge that is transmitted from generation to generation as part of a living tradition and that knowledge that is awarded the stamp of approval of the government of the day. In this regard it is worth noting that after 1835 C.E. Ayurveda was subjected to “negative cultural appropriation” when the British promoted English literature and sciences, taught in the medium of English, within India, and actively discouraged and suppressed Indian literature, languages and sciences, including Ayurveda. Svoboda’s own alma mater, the Tilak Ayurved Mahavdyalaya of Pune, was started in 1933 as part of a pro-Indian, anti-British cultural resurgence.

Despite a century of suppression (which led to the loss of immense amounts of practical knowledge) Ayurveda refused to die, and soon that very Government of India that had once rejected it changed course and recognized it as a legal and legitimate medical system, thanks to which Svoboda was able to complete a course of study and after graduation and internship to be licensed in 1980 as the first-ever non-Indian vaidya.

The traditional “licensing system” for vaidyas was however a casualty of the legalization process. In the days before Ayurveda was recognized by the government, students would be tested by their Ayurveda gurus and would be permitted to practice only after those mentors had given them the go-ahead. This guru-disciple relationship had been the foundation of Ayurvedic education since the beginning of Ayurveda, and negating it (however practically desirable this might be in the context of the modern world) transformed the question of possible cultural appropriation, since now admission into an Ayurveda college depends not on locating a knowledgeable, experienced guru (as Caraka mandated) but rather on completing the formalities demanded by the government, which has taken on itself the role of guru.

While in order to study Ayurveda in the past all three authors would have been obligated to convince a guru to accept them as students, in this new dispensation only the government needs to be convinced. This permitted Ramkumar (as an Indian national) and Svoboda (as a foreigner who happened to meet the right people at the right moment) to be admitted into colleges of Ayurveda but prevented Welch from doing so, despite her attempting for a full year to gain admission into more than one institution.

Over the past 40 years the Government of India has licensed as vaidyas many more non-Indians and now actively encourages foreigners to study Ayurveda. Many Indian students and practitioners of Ayurveda are moreover Christians, Sikhs, and Muslims. Welch’s guruji, who practiced as a vaidya in his early years, was born into a Sikh family and once told Welch that his teacher of Ayurveda had been a Muslim gentleman. This demonstrates the potential of vaidyas to come not only from outside a certain caste, but also not to be limited by a certain religious tradition.

We believe that these facts demonstrate that a substantial proportion of the population of the world’s largest democracy do not feel that non-Hindus and non-Indians who learn Ayurveda are inherently guilty of cultural appropriation. The question that remains is this one: Who should, according to Ayurveda’s traditions, be allowed and supported to study, practice and teach Ayurveda?

To help us address this issue we will make use of the means of acquiring knowledge that are universally accepted in Ayurveda: direct perception (pratyakṣa), testimony from authority (śabda) and inference (anumāna). Employing pratyakṣa and anumāna we find the following:

- We can perceive (pratyakṣa) that people with any skin color born or raised within or outside of India possess every level of knowledge of and facility with Ayurveda, from no knowledge to a modest amount of knowledge (e.g. having taken a one- or two-year program in Ayurveda and taken a trip or two to India to experience or learn more), from people that who have grown up exposed to or practicing certain Ayurveda principles but have no formal training to people who have enjoyed a lifetime of study and practice. These facts lead us to infer (anumāna) that the country in which one is born or educated is not a valid factor for determining who has the potential to become proficient in Ayurveda.

- We can observe (pratyakṣa) that some people with modest knowledge and little to no clinical practice who are unaware of how much they don’t know still present themselves as experts, regardless of country of origin or color of skin. We have heard concerns in the field that this practice threatens to distort and dilute the knowledge of Ayurveda.

To address these issues further, we turn to testimony from authority (śabda):

Authority is the statement of the credible persons (āpta). Āpta[s] are those who possess knowledge devoid of any doubt, indirect and partial acquisition, attachment, and aversion. The statement of persons endowed with such merits is testimony. Caraka Saṃhitā:Vimānasthāna:IV:4

According to Caraka, reliable authorities are those who are free from excessive mental or physical activity or stimulation, free from slothful, inert, hedonistic tendencies, and who are not attached to a particular outcome. Furthermore, they must be expert in their discipline and spiritually enlightened, and their knowledge must be universally true, in the past, present and future.

Clearly it is difficult now to find individuals who fit this description. But classical texts in India are understood to have been written by sages who did and thus, while recognizing that there are limitations, the texts themselves are considered authoritative. Moreover, though the experts of today may not qualify as āpta under Caraka’s definition, there is still value to be had in listening to those who have spent a lifetime trying to live up to this definition, and who have pondered deeply over how best to practice or propagate Ayurveda.

In answering the question of who should be allowed to learn, practice and teach Ayurveda, therefore, we conclude that in addition to examining authoritative texts we ought to consult the most experienced authorities we can find.

Directives From Authoritative Classical Texts & Authoritative Human Beings

It is our experience that, as stated in the article, “Vaidya-scientists: catalyzing Ayurveda renaissance”, “Ayurveda and biomedical sciences share the same spirit of open and sincere scientific enquiry.” Perhaps the reason for this is that, in the classical literature of Ayurveda, yoga and tantra, emphasis is placed neither on the color of your skin, the country in which you were born, your religion nor your gender. Significant emphasis is, however, placed on the qualities an individual student or teacher of these subjects should possess in order to be deserving of studying, practicing or teaching. Here are some references:

Given that the Brahma Sutras give the attributes of the Vedas as apauruṣeya (not of human origin), anādi (without beginning), ananta (without end) and sanātana (eternal), and that, as its name suggests, “Ayurveda” originated from the Vedas, logic permits us to conclude that though humans may compose treatises on the subject of the Veda of Life (Ayurveda), the knowledge itself is innate to the cosmos, an eternal vidya that is beyond the bounds that limit humanity.

As such, a student of Ayurveda is expected to possess some ability to align with this vidya. In ancient times students were accepted by a teacher only after strict scrutiny of their physical and mental qualities and behavior. Regarding the qualities expected in a student the Ayurvedic text Aṣṭāṅga Saṅgraha says:

A student who is devoted to (serve) the teacher, who has a keen desire to study, endowed with great intelligence, memory and talent; whose face, mouth, nose and eyes are normal and pleasant to look at, who is a brahmacari (celibate), who can withstand extremes (of heat and cold &c), who is courageous, virtuous and steadfast, who has exhibited these qualities to the teacher for over six months, who is pure (in talk), humble, reserved in behaviour, clean and endowed with many other good qualities should be initiated (for study) and taught till he attains mastery in the science and professional activities. Aṣṭāṅga Saṅgraha: Sūtrasthāna:II:2-3

In the chapter dealing with rites of formal initiation of a pupil into the science of medicine, the Suśruta Samhita says:

Such an initiation should be imparted to a student belonging to one of the three twice-born castes [brāhmaṇa, kṣatriya and vaiśya], who is of tender years, born into a good family. He should be possessed of a desire to learn and of strength, energy of action, contentment, character, self-control, a good retentive memory, intellect, courage, purity of mind and body, and a simple and clear comprehension. He should command a clear insight into the things studied, and should be found to have been further graced with the necessary qualifications of thin lips, thin teeth, and thin tongue, and possessed of a straight nose, large, honest, intelligent eyes, with a benign contour of the mouth, and a contented frame of mind, being pleasant in his speech and dealings, and usually painstaking in his efforts. A man possessed of contrary attributes should not be admitted into (the sacred precincts of) medicine. Suśruta Saṃhitā:Sūtrasthāna:II:2

Taken literally, this passage, among others, would seem to limit instruction in Ayurveda to individuals who follow varṇa-āśrama-dharma, and not to mlecchas (literally, those who “speak indistinctly” = do not know Sanskrit). Caraka, however, takes the concept of “twice-born” and extends it further:

After completing training, it is the third birth of the physician, for no one carries the title, “vaidya” by right of birth. On completion of training, the spirit of the Creator or of a rishi certainly enters into him. Henceforward the physician is known as, “thrice-born”. Caraka Cikitsāsthāna:I(4):52-53

We learned from our teachers that it is better to think of many of the statements in the texts as being normative, i.e. to establish norms to which all students should strive to cultivate. From this point of view every soul has the potential to develop and nurture the nature of the “thrice-born,” — emphasis being on each developing strong character and striving to live up to the highest ideals for a practitioner.

Ayurveda is not alone in this; most śāstras expect similar attributes in students. Here is what Siva Svarodaya has to say on the subject:

This science of svarodaya should be taught to a disciple whose nature is composed and pure, who is of good character and has firm faith in his guru, is obedient, and is obliged to the acts of kindness shown him. …It should not be imparted to one who is wicked, a nonbeliever, intemperate, of loose character, of an irritable nature and who commits adultery with his guru’s wife. Siva Svarodaya:14-15

The reason why such students should be chosen is so that the physicians that emerge from the course of study will stand out in their profession:

To be effective, the physician should possess excellence in theoretical knowledge, extensive practical experience, dexterity and purity. Caraka Saṃhitā:Sūtrasthāna:IX:6

The person who, despite being a patient, has a desire to live should avoid the physician who is devoid of the qualities mentioned earlier and who sells his treatments (for earning money), for such physicians are the forerunners of death. Aṣṭāṅga Sangraha: II:20

There are items of great interest in the above passages, all worth considering. But let us acknowledge that few, if any, modern students or teachers of the classical Indian sciences, within or outside India, possess all the prescribed qualities and adhere to all the prohibitions and guidelines. This is especially true if we consider the prescriptions for how and when Ayurveda should be taught and studied; prescriptions that include for example, the directive not to study it during on the new moon day, the eighth day of the fortnight of the waning moon, the fourteenth day of the dark fortnight, as well as the corresponding days of the bright fortnight: the day of the full moon, and at dawn and dusk, when we are unbathed, etc.

It does appear that what is regarded by the sages that authored the texts of Ayurveda as being most important in students is less how perfectly those persons fit the ideal description and more how diligently they learn:

A pupil who is pure, obedient to his preceptor, applies himself steadily to his work, and abandons laziness and excessive sleep will arrive at the end of the (studied) science. A student or a pupil, having finished the course of his studies, would do well to attend to the cultivation of fine speech and constant practice in the art he has learnt, and make unremitting efforts towards the attainment of perfection (in the art). Suśruta Saṃhitā:Sūtrasthāna:III:20

The beneficial and detrimental effects of weapons, scriptures and water depend on their user. A physician should therefore nourish his wisdom by abundant study and practice before treating. Caraka Saṃhitā:Sūtrasthāna:IX:20

This last quote is particularly noteworthy for two reasons, first the use of the words śastra and śāstra and second for its use of the word prajñā. “Hand-held weapon” is the meaning of śastra and “command, rule, precept” is the meaning of śāstra. As the two words come from related roots they can be regarded as being related, and there is little doubt that Charaka intended to emphasize this relationship. Surgical treatment literally involves weapons, and some medical treatments can be similarly intrusive. Study of a śāstra should never therefore be regarded as merely theoretical but always treated with the same respect that a warrior should show to a sharp sword. A “sharp sword” is often the image applied to prajñā, which means “profound wisdom”. The root cause of disease being prajñāparādha, only those vaidyas who have sharpened their wisdom to a fine edge can be relied upon to successfully address prajñāparādha and its causes. The duty of the vaidya is to continue studying the śāstra in order to augment and purify wisdom, and to gain the courage to wield that wisdom wisely, just as a weapon must be wielded. Here again, Ayurveda’s sages emphasize that meticulousness in study and adeptness in practice are the most important traits that students need to cultivate, regardless of how “ideal” those students might theoretically be. Of course, sometimes all these qualities are insufficient because of the cultural context in which one may find oneself–for example, those with darker skin are often marginalized and find extra obstacles in their educational path.

Vaidya Raghavan Thirumulpad, who studied and practiced Ayurveda in India in a traditional way throughout his long life and was awarded the title vaidyaratnam (“Gem among vaidyas”), believed that this knowledge was to be shared with all. He practiced the Gandhian concepts of trusteeship and sarvodaya: “Trusteeship implies that one’s wealth and knowledge should be shared with others and sarvodaya entails the upliftment of all.”

If we can agree that this knowledge can be shared with all, the question arises as to how to protect the integrity of the knowledge, i.e. how to prevent it becoming over-simplified or diluted as it spreads. Thirumulpad was neither ignorant of nor naïve to these risks but, rather than restrict the information from disseminating, emphasized that, “Systematic learning, understanding and propagation of Ayurveda will protect it from corruption during such transformation”. He taught that the integrity of śāstra (teaching) is maintained by the adhering to the following four steps:

- adhīti: perusal, study, absorption and recollection of the material

- bodha: gaining and internalizing the knowledge

- ācaraṇa: practicing the medicine and knowledge in our lives and with our patients

- pracaraṇa: teaching the knowledge to others.

As Patwardhan, Joglekar, Pathak and Vaidya write in “Vaidya-scientists: catalysing [sic] Ayurveda renaissance”, “The problem lies in jumping from adhīti to pracaraṇa without bodha and ācaraṇa, when teachers preach without practice.” When this happens teachings are bound to be diluted. By repeating the same pungent example twice Suśruta seems to be emphasizing the value of bodha in this passage:

The endeavors of a man who has studied the entire Ayurveda śāstra but fails to make a clear exposition of the same, are vain like the efforts of an ass that carries a load of sandalwood (without ever being able to enjoy its scent). A foolish person who has gone through a large number of books without gaining any real insight into the knowledge propounded therein is like an ass laden with logs of sandal-wood, that labors under the weight it carries without being able to appreciate its virtue. Suśruta Saṃhitā:Sūtrasthāna:IV:2-3.

It is not uncommon in the modern world to find people writing books on Ayurveda after very little training in the subject, much less significant clinical practice. As a counterpoint and example of devotion to ācaraṇa, we could look to Sun Si Miao (581-682 CE), famous physician, alchemist and author of two seminal 30-volume works on the practice Chinese medicine. He lived until age 101. Modern day 88th generation Daoist priest Jeffery Yuen has taught that Sun Si Miao began practicing medicine as a teenager and wrote his first book at 71 years old, after about 60 years of practice. At 90 years old he wrote a supplemental set of volumes to the first.

Related to ācaraṇa, Suśruta writes:

A physician having thoroughly studied the science of medicine, and fully pondered on and verified the truths he has assimilated, both by observation and practice, and having attained to that stage of (lucid) knowledge, which would enable him to make a clear exposition of the science (whenever necessary), should open his medical career (commence practicing) with permission of the king of his country. He should … walk about with a mild and benign look as a friend of all created beings, ready to help all, and frank and friendly in his talk and demeanor, and never allowing the full control of his reason or intellectual powers to be in any way disturbed or interfered with. Suśruta Saṃhitā: Sūtrasthāna:X:2.

Knowledge should thus be shared with those that will employ it according to the dictates of dharma and with a state of mind characterized by sattva. In this regard there still exist family or practitioner traditions that are meant to be kept secret, being made available to those who receive permission from the keepers of that knowledge to learn or teach it.

Caraka encouraged us not to use Ayurveda simply to earn a living but for the betterment of human welfare:

Ayurveda has been enlightened by the great sages devoted to piety and wishing immortal positions for [people’s] welfare and not for earning or enjoyment. Those who take up the treatment only for human welfare and not for earning or enjoying exceeds all and those who sell the regimens of therapy for livelihood are devoted to the heap of dust leaving aside the store of gold. Caraka Saṃhitā:Cikitsāsthāna:I:55-62

At the same time it is understood that not all are able to practice Ayurveda without needing to earn a living. As Ramkumar observes, “White, black, brown: none of this should matter. If Ayurveda teaching and healing is being traded for money today, anybody who has the wisdom and healing touch should be able to do so. The line between dharma and adharma today would rest on whether it is for ‘need’ or for ‘greed’.”

Caraka agrees, in his final precept for dinacaryā:

One should take up those means of livelihood which are not contradictory to dharma. Likewise, he should pursue a life of peace and study. Caraka Saṃhitā: Sūtrasthāna:V:104

One area where the issue of cultural appropriation does seem to us to be significant is within the issue of commercialization of Ayurvedic knowledge, particularly in the realm of biopiracy and intellectual property rights. Because our authoritative sources teach that the knowledge of the Vedas belongs to everyone (or to no one), any “copyright” or trademark” on this knowledge would run contrary to that spirit. By rendering it more difficult for others to study or practice Ayurveda, this would constitute adharma. For example, companies in various countries have attempted to patent such widely used Indian herbs as neem and turmeric. Had such efforts been successful they would have made it difficult for people within India to produce, sell and use these plants without restriction. Thankfully, these efforts were defeated in the courts of India.

We learned from our teachers that we must be wary of prejudice of any kind. “Historically, Ayurveda has been progressive and inclusive, adopting an integrative approach to other systems.” As stated in Caraka Saṃhitā:

The science of life shall never attain finality. Therefore, humility and relentless industry should characterize your endeavour and approach to knowledge. The entire world consists of teachers for the wise. Therefore, knowledge, conducive to health, longevity, fame and excellence, coming even from an unfamiliar source/enemy, should be respectfully received, assimilated and utilized. Caraka Saṃhitā:Vimānasthāna:VIII:14.

What does become questionable, particularly from the standpoint of cultural appropriation, is the problem of cultural context. Ayurveda originated in India and much of its knowledge exists within an Indian cultural context. Ayurveda itself can be damaged when people from other cultures attempt to use or, worse, teach this knowledge while ignoring its context. We take the mispronunciation of Sanskrit as a specific example.

Sanskrit

Many traditions of Ayurveda exist in India, not all of them expounded in Sanskrit. But today professionalized Ayurvedic education, in India and abroad, is based on ancient Sanskrit texts, and having some knowledge of that language is essential to all-round comprehension of the science.

Sanskrit is more properly samskṛta, which literally means “well-constructed”. Sanskrit pronunciation is not arbitrary. Sanskrit is an engineered language, one that when properly pronounced can convey more than the surface meanings of the individual words. It is not easy even for modern Indians to pronounce correctly, much less for those who have not grown up speaking an Indian language.

This situation is complicated further by the fact that Sanskrit words written in Roman script often lack the diacritical marks that identify which letter is being transliterated. Therefore, if one doesn’t already know the word, it may be impossible to know the correct pronunciation without researching it.

Dr. Fred Smith, Professor of Sanskrit and Classical Indian Religions at the University of Iowa, comments on the correct pronunciation of Sanskrit:

“I divide up [“correct” pronunciation] into North Indian, Western Indian, and South Indian, with variants in eastern India, albeit not as noticeable. The biggest problem with non-Indian pronunciation of Sanskrit words, largely found in the Anglophone world and in European languages, is the tendency to place a word’s emphasis on the penultimate syllable. This is not the case in Sanskrit, where the stress goes to whichever syllable closest to the end of the word has a long vowel or conjunct consonant. Thus Rāmāyaṇa, has the emphasis on the -mā- and Mahābhārata on the -bhā-, and so on. Among westerners there’s a near total lack of awareness of long and short vowels in Sanskrit, proper inflection of aspirated consonants, and the clear distinction (at least to Indians and trained scholars and Indophiles such as me) between retroflex and dental consonants (-ṭa- and -ta-, etc.). Beyond that there are different ways of articulating -jña-: -gya- in Hindi influences North India, -dnya- in Maharashtra & Gujarat, -gna- in South India. Sometimes, in Bengali or Oriya influenced eastern India, the distinction is lost between ṣ/ś and -s-. Same in Tamilnadu. Also, the pronunciation of -v- > -va-, -vi-, etc., shifts between -v- and -w-. Neither are incorrect Usually at the beginnings of words v- is used, but in composition following another consonant, it will shift to -w-, as in tvam > twam, śva > śwa, sva > swa. Intervocalically, it will always be a straight -v-, as in avatāra, eva, etc. Bengalis will always pronounce v- as b-. No problem. The tendency to pronounce -ph- as -f- is found often in India, especially in Urdu-influenced Hindi. This has leaked into European and Anglophone pronunciation, albeit unsystematically. The rule for non-Indians seeking to pronounce Sanskrit correctly should be to use -ph- (aspirated) whenever possible. Similarly, speakers should restore the short -a- at the ends of words, almost always left off by Hindi speakers. That’s the short story. What this adds up to is that there are only a few ways to pronounce and many ways to mispronounce Sanskrit, so long as there is sufficient training.”

To summarize, the big problems with non-Indian pronunciation of Sanskrit words are:

- the tendency to place a word’s emphasis on the penultimate syllable

- lack of awareness of long and short vowels

- lack of proper inflection of aspirated consonants

- lack of clear distinction between retroflex and dental consonants

- failure to use the short -a- at the ends of words

The intrinsically phonetic nature of the Sanskrit language means that these are not trivial concerns. For those who know the devanāgarī script, this video can assist you to refine your pronunciation.

On multiple occasions we have heard people—from the very modestly to the very well educated in Sanskrit– grossly or mildly mispronounce Sanskrit terms or words–even leaving out entire syllables, yet still feel quite confident about their pronunciation. Mispronunciation in itself does not negate the value of what is being taught. Welch notes that she has, “studied from some of these individuals–people who nonetheless had deeply studied the theory and practice of various lineages, and who conveyed the teachings in enlivened ways”. It does, however, betray a degree of ignorance of the language.

Though the texts of Ayurveda we use are written in Sanskrit, usually in the devanāgarī script, Ayurveda does not need to be taught in that language and it is not essential that students of Ayurveda learn to read and write the devanāgarī script, nor to learn an accurate method of transliteration. However, without doing so, we are all but guaranteed to consistently mispronounce Sanskrit words. One notable mispronunciation is applied to the very word “Ayurveda”, with Western students, practitioners and teachers often pronouncing it “Are-you-veda” when the accurate pronunciation is “Ahh-yoor-veda”. It is our hope that those teachers of Ayurveda who choose to use Sanskrit in their teaching will make serious efforts to refine their own pronunciation and will, if they are not entirely confident in this regard, let their students know that, while they have made sincere attempts to articulate correctly they may well make mistakes for which they request forbearance from their students and forgiveness from the language.

Chanting mantras and songs in Sanskrit introduces an additional layer of complication in the form of chandas, or metrics. There are a number of different meters, some of which are complex, and the rules for Vedic chanting are much stricter than for classical texts. For some hymns rhythm and melody are strictly fixed; for others, anything goes. What is critical is to know which can be altered and which cannot, and it grates on the practiced ear to listen to someone who tries to sing or recite a chant without following the traditional style, particularly if it is mispronounced and out of tune and rhythm as well.

Our point here is a simple one: we have been taught that anyone who elects to use Sanskrit should respect it sufficiently to endeavor to learn how to use it properly, just as anyone who elects to use Ayurveda should endeavor to do the same.

Conclusion

We conclude by acknowledging that we may be mistaken in our opinions, and that our perspectives on these matters may evolve. We have each learned to see things from perspectives based on our teachers and lineages, but may have learned things incompletely. We take refuge in their counsel and in their invitation to us to learn what and how we have. We each rest on the shoulders of our teachers, learning from them at their invitation, whether they are teaching us for profit or not. It is up to us to learn, practice and teach while making honest, sincere attempts to live up to the guidance of our teachers and to cultivate the qualities that the classics direct us to develop.

Below are some resources that explore experiences of cultural appropriation related specifically to Ayurveda. If you know of other sources or perspectives, let us know:

Interview with Susanna Barkataki: Ayurveda, Yoga + Cultural Appropriation

Svādhyāya & Black Lives Matter: Healing The Wounds Of Inequity by Claudia Welch. While not about cultural appropriation in Ayurveda, this explores some questions and responses related to issues of racism that can cause harm, and how white people might begin to apply an Ayurveda perspective to do less harm. This article includes a more extensive list of resources at the bottom of the article.